Education in the Poarch Creek Community — From Barriers to Breakthroughs

Share this:

In honor of Native American Heritage Month this November, the Poarch Creek Indians will share weekly stories that celebrate key aspects of the Tribe’s culture, history, and a fresh look at the future.

During Native American Heritage Month, we remember those who fought to make education possible for our community. One of those people was Homer Jack Daughtry, a Poarch Creek man whose courage helped ensure that Native children in South Alabama could attend school despite widespread efforts to deny them that right.

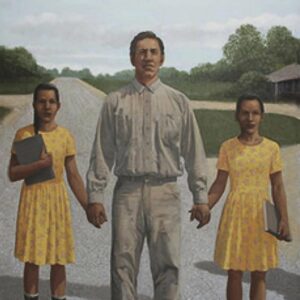

Illustration of Jack Daughtry and his two daughters.

Born in 1901, Jack Daugherty grew up amid financial hardship and discrimination, which limited his formal education to only the third or fourth grade. Despite these challenges, he developed a deep sense of responsibility to his community.

By the 1930s and 1940s, as Indian schools began closing, many Creek children were left without access to education. Determined to change that, Jack purchased a bus to transport students from outlying areas to the Indian Consolidated School in the Poarch Community. His determination and generosity gave dozens of Creek children the opportunity to continue their schooling when few options remained.

Former Poarch Creek Consolidated Schoolhouse.

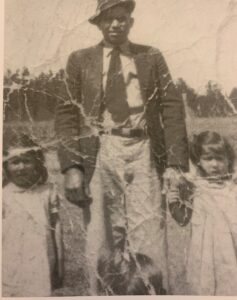

In 1947, when a public-school bus driver refused to pick up his twin daughters, Jack stood in the road until they were allowed to board. This act of courage became a lasting symbol of the fight for equal rights faced by the Poarch Creek people and Native communities across the South.

Working alongside Tribal leader Calvin McGhee and others, Jack helped pave the way for generations of Poarch Creek students to receive an education that earlier generations were denied. His legacy lives on in every Tribal Citizen who walks across a graduation stage.

Students in class at the Fred L. McGhee Early Learning Center.

We honor Jack’s courage and the enduring spirit of our community – because his story is our story.

Jack Daughtry and his two daughters, Perline Daughtry McGhee and Earline Daughtry Coleman.

“Granddaddy Jack and Tracy Rolin, ‘Uncle Tom,’ tried very hard to have the consolidated Indian school extended beyond the sixth grade to include the twelfth,” said Clayton Coon of the Tribal Historic Education Department. “They understood that many Indian students would face serious challenges graduating from high school in Escambia County. Today, I still stand in support of the vision they had in the 1940s—to have our very own high school dedicated to the education of our Tribal children.”